On April 24, 2013, a tragic incident sparked international debate about the responsibilities of corporations and consumers toward laborers and their communities in faraway places. The Rana Plaza building in Dhaka, Bangladesh, collapsed due to structural failure, killing at least 1,130 people, and injuring more than 2,500.[1] It housed five garment factories that manufactured for brands such as Primark, Benetton, JC Penney, and Walmart.[2] Yet these workers were paid as little as 45 cents an hour to work in sweatshop conditions — often while subjected to physical and sexual abuse.[3]

Figure 1: Rana Plaza building collapse.[4]

The conversation about the Rana Plaza incident and general labor exploitation and trafficking has motivated me to work on developing a potential framework for an international convention on standardizing and codifying corporate responsibility.

In this post, I would like to present a clearer picture of the current state of global value chain (GVC) discourse and where I believe the future of it lies, as informed by my Fulbright work and studies.

The Individual Consumer Approach

The current scholarly debate about GVC sustainability can be structured in one of six ways, or some combination thereof. Each approach places the onus on an actor: the consumers, corporations, Global South nation states (where abuses are centralized), or an idealized world trade system. Still others envision a worker-led corporate accountability system or a voluntary Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) schema.

While I think none of the six approaches has a monopoly on the “right way forward,” I think each is a necessary facet of it. My interest in an international convention is a result of frustration with the over-emphasis on the individual consumer model — itself largely the result of public frustration with the lack of an enforceable approach to corporate accountability.

The consumer approach places the responsibility on consumers, stating they have a duty to not participate in exploitative trade, and instead should buy fairly-traded products. While the dedication of the consumers who hold this view is commendable, my concern is that international reliance on the consumer model would be to tolerate the oversimplification of the vast complexity of GVCs and the gross imprecision of its effects.

To give a taste, it took Intel more than four years to understand its own supply chain well enough to ensure it had no Congolese tantalum,[5] a conflict mineral reliant on child labor and abuse.[6] The argument that fair trade labels can condense and communicate all a consumer needs to know to make ethical purchases is untenable. Further, certification naturally deflects from other issues. For instance, if a factory is audited for labor exploitation, it might not be audited for workplace safety, or vice versa — but labels do not relay nuance. Additionally, the certification business is a multi-million dollar privately-run industry spurred on by corporations’ profit motive, making it appear even less accurate or trustworthy.

Aside from the oversimplification of GVC complexity, the consumer approach is imprecise. Specifically, there is no inbuilt proportionality mechanism or way to pinpoint the offending target(s). Even scholars who support this approach admit that it may have potentially disastrous results for laboring communities (whose primary source of income was that industry), thereby increasing their vulnerability to other, perhaps worse, exploitation. Some proponents resolve this conflict by proposing that better-off individuals in developed countries should provide monetary aid and direct service provision to the poorest workers in such societies. Although this could be a temporary measure for dire circumstances, long-term use increases foreign aid dependence, rather than encouraging sustainable self-sufficiency and lasting poverty alleviation.

While there are about six distinct ways to conceptualize combatting abuses in GVCs, the consumer approach overemphasizes how much the individual consumer can know and overestimates how efficacious it can be.

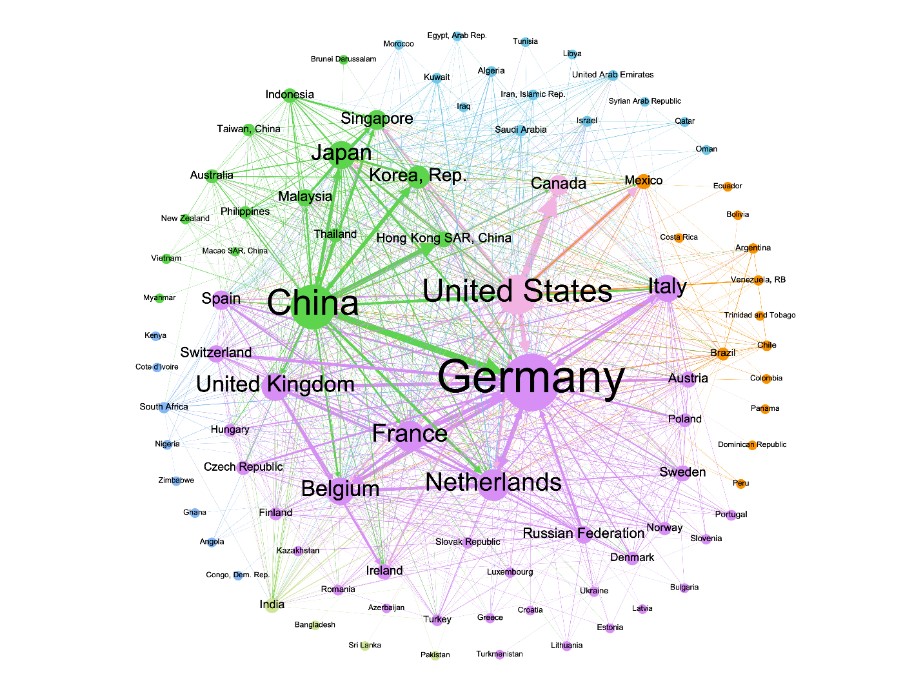

Figure 2: A Global Value Chain participation network, 2019.[7]

A Way Forward, Informed by my Fulbright Work and Studies

When I was applying for Fulbright, the United Nations had, just prior to this, called for guidance in addressing problems regarding the nexus of business and human rights.[8] From my background in anti-human trafficking and employment law work, I knew this project at the intersection of human rights, labor, and business law was something on which my efforts should be centered.

My Fulbright fellowship has been crucial to this work in at least three ways. It has afforded me the opportunity to work as a research fellow with the TraffLab Project (European Research Council), a multidisciplinary anti-human trafficking research effort. My work as a research assistant for the Chief Investigator, Dr. Hila Shamir, and as an assistant editor of the forthcoming book, Modern Slavery and the Governance of Global Value Chains, has been incredibly enriching to my experience. Second, Fulbright has opened the doors for my international business law LL.M studies at Tel Aviv University, a leading academic institution for comparative law in a global center of trade and business. Third, I have been matched with Orna Lin & Co., a premier employment law firm in Israel, as part of Tel Aviv University’s “GloCal” Program, to conduct comparative law research on a precedent-setting labor abuse and unionization case before the National Labor Court.

I mentioned above that none of the six approaches has a monopoly on the “right way forward,” but each is a necessary facet of it. My studies and work have confirmed this notion time and again.

I propose the most viable way forward would be to build an international law convention that places the burden on those best able to shoulder it — the corporations. However, it would also account for: the strengthening of Global South nation states’ economies, and their measures for workers’ protection and redress; the needs and desires of workers themselves; corporate codes of ethics and voluntary charity-based CSR; and the ethical motivations of individual consumers who wish to “buy fair.”

My hope is that I will be able to contribute meaningfully to this field of GVC scholarship and be part of the change that leads to the end of grievous labor abuses, such as the one at Rana Plaza seven years ago.

References:

1. International Labour Organization (2017). The Rana Plaza Accident and Its Aftermath. [online] Ilo.org. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/geip/WCMS_614394/lang--en/index.htm [Accessed 23 Jan. 2021].

2. Clean Clothes Campaign (n.d.). Rana Plaza. [online] cleanclothes.org. Available at: https://cleanclothes.org/campaigns/past/rana-plaza#:~:text=With%20our%2…. [Accessed 23 Jan. 2021].

3. Karim, N. (2019). Six years after Bangladesh’s Rana Plaza disaster, fashion brands urged to pay more. [online] reuters.com. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bangladesh-labour-fashion/six-years-… [Accessed 23 Jan. 2021].

4. International Business Times (n.d.). Crowds Gathering Around Rana Plaza Collapse. IB Times. Available at: https://d.ibtimes.co.uk/en/full/1375502/crowds.jpg [Accessed 23 Jan. 2021].

5. Crawford, K. and Joler, V. (2019). Anatomy of an AI System: The Amazon Echo as an Anatomical Map of Human Labour, Data and Planetary Resources. Virtual Creativity, [online] 9(1), pp.117–120, XI. Available at: anatomyof.ai [Accessed 2 Jun. 2020].

6. Bureau of International Labor Affairs (2018). Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor - Democratic Republic of the Congo. [online] DOL.gov. Available at: https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor/congo-d… [Accessed 23 Jan. 2021].

7. Goff, S.C. (2016). Fair Trade: Global Problems and Individual Responsibilities. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 21(4), p.539.

8. United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (n.d.). OHCHR | B-Tech Project. [online] www.ohchr.org. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Business/Pages/B-TechProject.aspx [Accessed 23 Jan. 2021].

Articles are written by Fulbright grantees and do not reflect the opinions of the Fulbright Commission, the grantees’ host institutions, or the U.S. Department of State.